Continuing the discussion from the last post, this is a look at the soldiers and Roman centurions found in the Luke-Acts narratives. There is much to be learned for the contemporary combatant through these texts.

Receiving the kingdom of God and living a life of repentance does not include repudiating life in the military. Rather, embracing the path of God transforms how a warfighter must operate within the confines of his vocation. To the godly warrior belongs the imperatives, “Do not extort money from anyone by threats or by false accusation and be content with your wages” (Lk 3:14).[1] Self-control, vocational discipline, and resting in the promise of the provision of daily bread are essential for the combatant who would please God.

The narratives of Luke-Acts reveal many soldiers who please God. The man who stunned Jesus with his faith and put the Israelites to shame was a Roman centurion, a high ranking commander with a large troop underneath him (Lk 7:1-10; Matt 8:5-13).[2] His experience in the military provided him a profound understanding of authority, obedience, and submission. His pursuit of Jesus conveys his sense of compassionate responsibility for the weak. This warfighter is held up as a model of humble faith, strong trust in God’s capability, and care for those under his charge.

In Luke’s crucifixion narrative, the hand that held the hammer was a Roman soldier. He was at the bottom of the chain of command, fulfilling the order of Pilate as a man who was under orders, but who was also a moral agent. Duane Larson points out that his statement, “certainly this man was innocent” (Lk 23:46), is an unsanctioned acknowledgement that “his victim was right and the cause for which he killed him was wrong.”[3]

Here, the reader finds an unexpected example of navigating moral dissonance, owning heinous actions and publicly declaring what is true and right no matter the consequence. Larson further states, “The centurion’s words are expressed in the context of his participation in what he considers an unjust act, and a candid expression of his conscience sorting out the conflict between his values and the performance of his duty—from the point of view of his victim.”[4]

In Acts, the centurion Cornelius is described as a devout man, a God-fearer, a spiritual leader of his household, a man of generosity and regular prayer (Acts 10:2). Apparently, his piety garners divine attention (Acts 10:5).[5] The narrative focuses on the reception of a vision, which reveals a warrior who is sensitive to God’s voice and direction (Acts 10:3-6).

Cornelius was a man who understood the chain of command and submission to orders: he responded with instantaneous obedience to God’s command (Acts 10:7).[6] Furthermore, the narrative points to Cornelius’s humble reception of God’s word and obedience in baptism (Acts 10:33, 48). Cornelius demonstrates that robust faith and spiritual discipline are not contrary to vocational warfighting. He models the critical link between family health and warrior health, and exemplifies humility, obedience, generosity, and prayer.

Centurions and soldiers show up again in Acts 23:10-35 where Paul’s life is at risk on two occasions (Acts 23:10,12). In both scenarios, warriors stepped up to protect and defend Paul (Acts 23:10, 17-18, 31). The point to draw out is that warriors served “as moral agents of justice, and competently did their jobs regardless of whether their motivations were ‘perfect.’ They didn’t allow the violent robbing of another life when they could have turned away.”[7]

In Acts 27:1-43, a Roman centurion becomes the main focus of the story during the narrative that describes a shipwreck and survival. The centurion’s role was to escort Paul and a number of prisoners to Rome. He treated Paul with kindness (Acts 27:3), responded to Paul’s word from God with respect (Acts 27:31-32), and saved the lives of Paul and others when they were in peril (Acts 27:42-44).” The centurion was valiant in the face of the shipwreck, risking life and limb to fulfill his duty. “His actions reflect what soldiers do; they accept risk and find a way to succeed under duress in the midst of chaos.”[8]

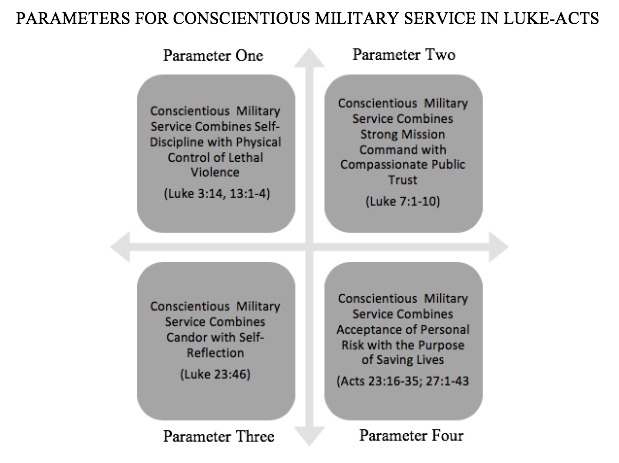

Luke-Acts provides important glimpses into the intersection of faith and the vocational warfighter. More than providing mere examples of godly warriors, “these texts are much better understood … as narratives whereby soldiers’ moral senses and the Bible’s transcending symbols become interactive partners that guide soldiers’ moral reasoning and conscience.”[9] Within these stories, warriors find guidance for applying their craft alongside their faith. From the key centurion/soldier texts in Luke-Acts, Duane Larson suggests four parameters or guidelines for conscientious military service captured in the table below.

[1]“This is the only place in the Bible where soldiers ask existential questions about vocation, ‘What does God require from us?’ and receive a direct answer from God’s messenger.” John the Baptist “makes soldiers’ rights and duties to the military force subject to God’s transforming, reconciling and visible kingdom. This subjection includes how soldiers view themselves and how they practice their craft.” Duane Larson and Jeff Zust, Care for the Sorrowing Soul: Healing Moral Injuries from Military Service and Implications for the Rest of Us (Eugene: Cascade Books, 2017), 170-171.

[2]“The centurion texts in Luke and Acts convey a treasure trove of meaning for modern soldiers concerned with how most responsibly to steward their vocation. These texts parlay vital biblical concepts into narratives that can illumine anew one’s own situation and provide means for understanding the whole canon. Some interpreters may be tempted to use the centurions of Luke/Acts as character studies to provide ideal, prescriptive examples for conduct. These texts are much better understood, however, as narratives whereby soldiers’ moral senses and the Bible’s transcending symbols become interactive partners that guide soldiers’ moral reasoning and conscience.” Luke-Acts provides important insight into the warfighter’s spiritual responsibilities as “each engagement is a ‘snapshot’ of the spiritual dimension of vocational military practice…these Roman soldiers provide a transformative word to any modern soldier who seeks to understand stewardship of service to God and service to nation.” Larson and Zust, Care for the Sorrowing Soul, 166-167.

[3]Larson and Zust, Care for the Sorrowing Soul, 184.

[4]Ibid., 187. It is noteworthy that the warrior’s self-condemnation and declaration of Christ’s innocence is framed as an expression of “praise” (Lk 23:47). The term ἐδόξαζεν is characteristic for the act of glorifying and worshipping God (Lk 5:25-26). Calvin comments, “When Luke represents him as saying no more than certainly this was a righteous man, the meaning is the same as if he had plainly said that he was the Son of God, as it is expressed by the other two Evangelists. For it had been universally reported that Christ was put to death, because he declared himself to be the Son of God. Now when the centurion bestows on him the praise of righteousness, and pronounces him to be innocent, he likewise acknowledges him to be the Son of God; not that he understood distinctly how Christ was begotten by God the Father, but because he entertains no doubt that there is some divinity in him, and, convinced by proofs, holds it to be certain that Christ was not an ordinary man, but had been raised up by God.” John Calvin, Commentary on the Synoptic Gospels (Grand Rapids: Christian Classics Ethereal Library, 1999), 227. Christopher B. Zeichmann, The Roman Army and the New Testament (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2018), xix. Zeichmann would challenge taking anything positive from this narrative and character. He argues that the New Testament posture toward Roman soldiers is primarily “ambivalent” although he concedes that there is complexity in the narratives. The fact that there are clearly positive and negative portrayals creates an inescapable tension in the New Testament.

[5]“The angel responded by noting that God was aware of his piety. His prayer and his acts of charity had gone up as a ‘memorial offering’ in the presence of God. The term ‘memorial’ (literally, ‘remembrance,’ mnemosynon) is Old Testament sacrificial language. Cornelius’s prayers and works of charity had risen like the sweet savor of a sincerely offered sacrifice, well-pleasing to God (cf. Phil 4:18). The importance of Cornelius’s piety is reiterated throughout the narrative (vv. 2, 4, 22, 35).” John B. Polhill, The New American Commentary: Acts (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1992), 253.

[6]Of note, Cornelius the devout centurion obeys God’s instruction to send for Peter by sending a devout soldier under his authority (Acts 10:7).

[7]Larson and Zust, Care for the Sorrowing Soul, 189.

[8]Ibid.

[9]Ibid, 166.